-

-

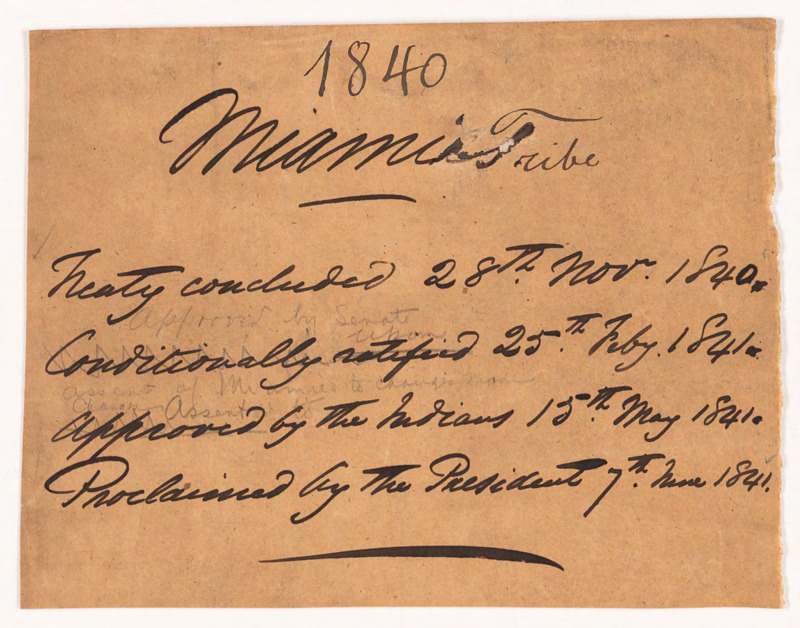

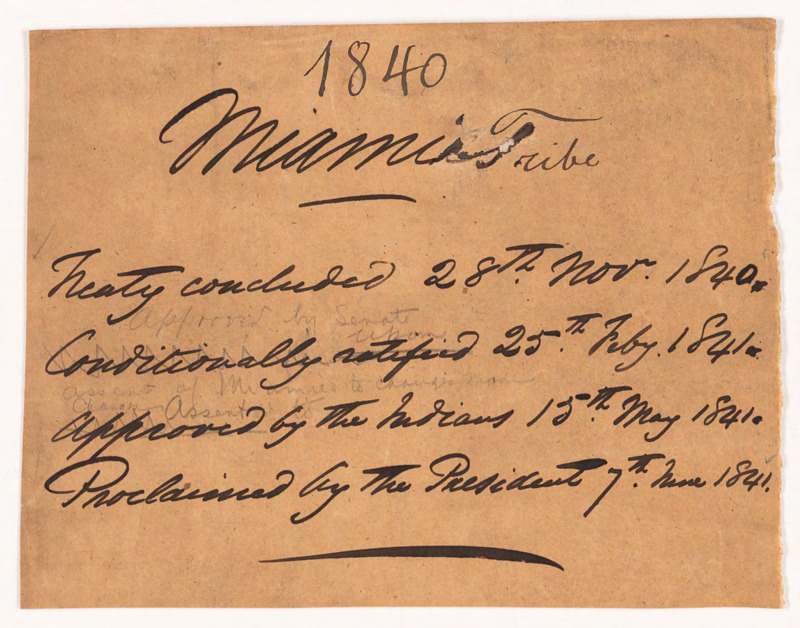

The Treaty of the Forks of the Wabash, signed in November of 1840 by the Myaamia and the U.S. government, marks the point in time when Myaamia leaders, for reasons still unknown, yielded to the unrelenting pressure of the U.S. government to leave their homeland. This treaty relinquished their reservation in Indiana in exchange for a reservation of the same size (500,000 acres) west of the Mississippi in what would later become the Kansas Territory, as well as stipulated that the Tribe would move to the new reservation within 5 years of the agreement. The Myaamia resisted this removal for six years, hoping to remain on individual family allotments that had been created decades prior and retain their essential cultural connection to their land. However, the expulsion began on October 6th, 1846 with the forcible loading of hundreds of Myaamia by the U.S. Army into canal boats leaving for the Kansas Territory. To provide perspective; as these canal boats passed through Cincinnati, mere miles away, Miami University students participated in classes, joined the first fraternities, and debated topics in literary societies like the Miami Union and the Erodelphian.

-

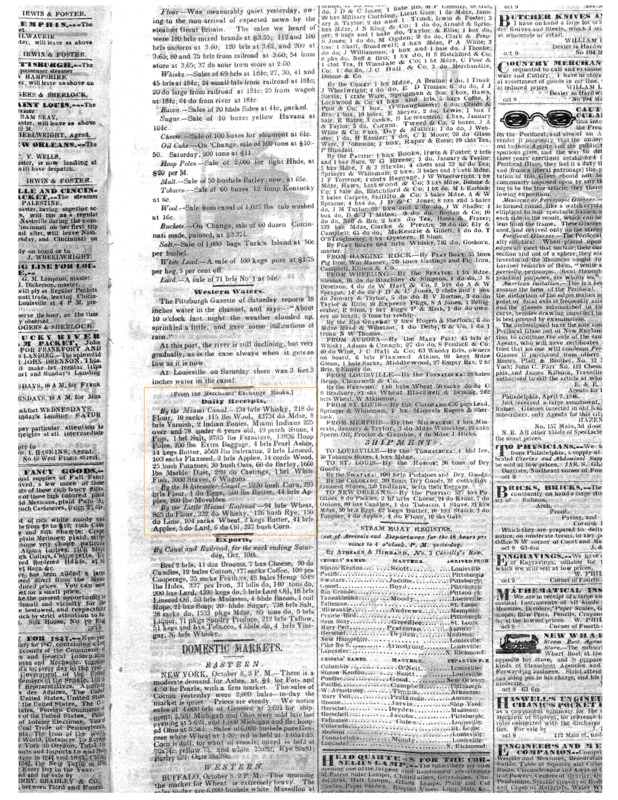

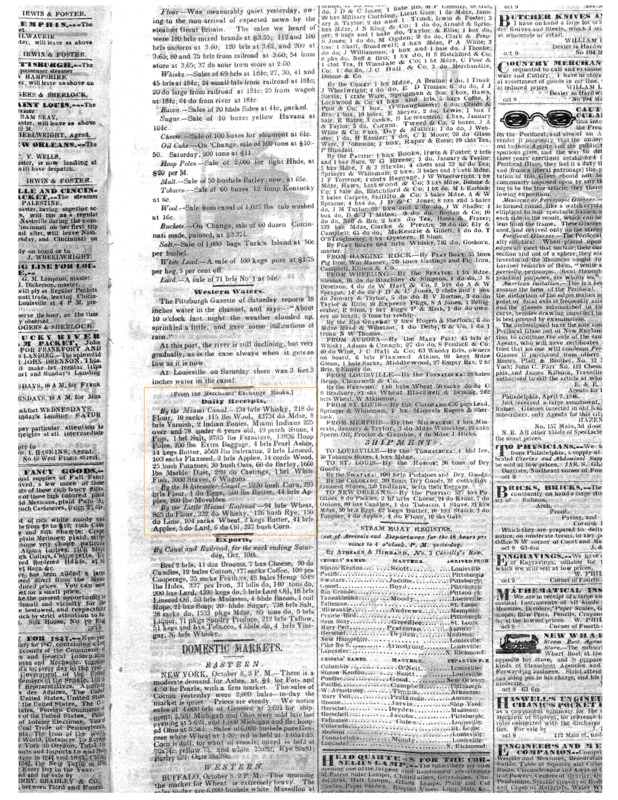

On October 11th, 1846, just 5 days after the beginning of the Myaamia removal by the U.S. government, five canal boats carrying several hundred Myaamia people arrived in Cincinnati, OH by way of the Miami-Erie canal. In Cincinnati, they were forcibly moved to the Steamship Colorado and began their journey west on the Kaanseenseepiiwi (Ohio River) towards St. Louis, their next stop along the route towards the Unorganized Territory (Kansas), which would be their final destination for the next couple decades. The day after their departure, it was reported in the Cincinnati Gazette’s “Daily Receipts by the Miami Canal” that “Miami Indians 225 over and 78 under 8 years old” had arrived in Cincinnati via the Miami-Erie canal, along with other “cargo” goods like potatoes, wool, and butter. This news clipping, as well as others like it, provide a striking example of how the U.S. government and its citizens thought of the Myaamia people as they forced them off their homelands, essentially attempting to strip them of their basic human identity and beyond through reporting tactics and other actions.

-

Individuals in the photo from left to right: Secretary Treasurer Donya Williams; Second Councilperson Scott Willard; Chief Douglas Lankford; First Councilperson Tera Hatley; and Second Chief Dustin Olds. This is a photo of the Business Committee of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma circa 2018. The General Council is the governing body of the Nation and the Council, under the authority of the Miami Constitution, elects 5 Tribal members to the Tribal Business Committee in order to conduct the day-to-day affairs of the Nation on behalf of the citizens. There are also a large amount of services provided for citizens: access to the Myaamia Activity Center, childcare, education support and scholarships, and social services, among others.

-

Northeastern Oklahoma is now the seat of government for the sovereign nation of the Miami Tribe. The Nation maintains a 1,400-acre land base and many tribal businesses in and around Miami, OK and through these establishments creates the resources necessary to maintain the integrity, both cultural and political, of the Nation. Through the establishment of the Cultural Resources Office, the Miami Tribe has taken responsibility for the status of their resources and, in full knowledge of the devastating effects of the many assimilation tactics forced on them by the U.S. government over the past 150 years, has recognized that their heritage language and cultural knowledge must be restored to the people so their identity as Myaamia will live on. The Cultural Resources Office works under the following areas of need: reclamation, restoration, revitalization, preservation, and perpetuation.

-

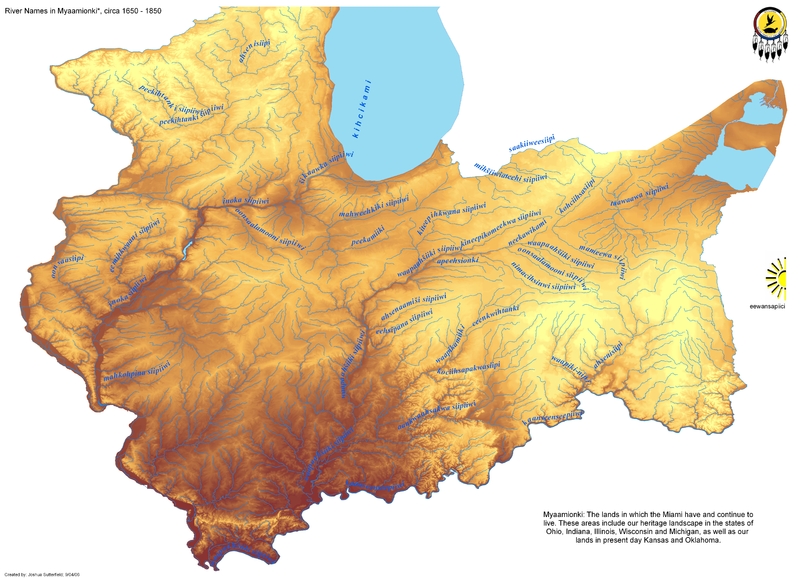

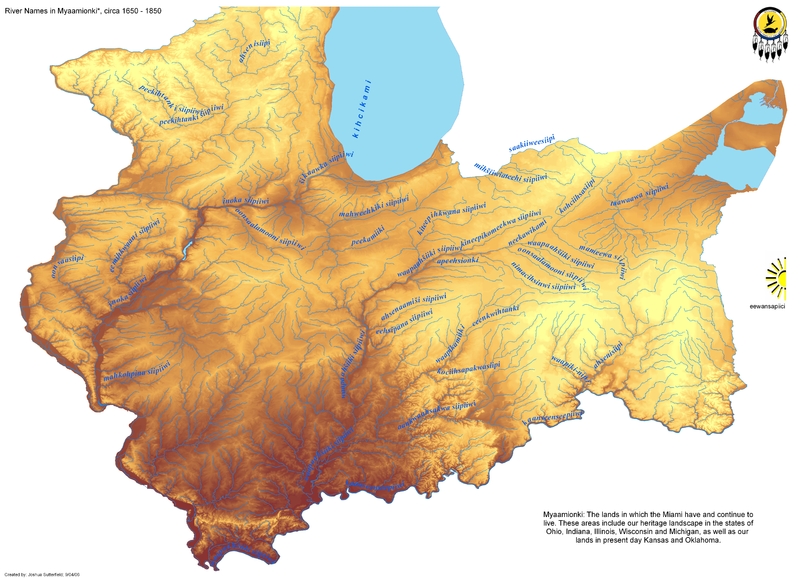

This map shows the Myaamionki, the homelands of the Myaamia people, which includes their heritage landscape in what is today the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Most villages were concentrated on the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi (Wabash River) between Kiihkayonki (Ft. Wayne) and Aciipihkahkionki (Vincennes). Myaamia forebearers regularly traveled, hunted, and gathered throughout this extensive, shared landscape. Prior to contact with Europeans, the people of each village had their own leadership and no village could command the allegiance of another. So, what connected these villages to form a group distinctive from other tribes in the area? Physically, the rivers and trails that crisscrossed the Myaamionki were the pathways by which communities were connected to each other. Culturally, it was the shared language, called ‘Miami-Illinois’ by linguists today, a common place, and a similar historical experience that connected this close-knit Myaamia family.